Author: Cello Kan

Percy Phang(彭學斌) is a name I’ve known for nearly 15 years. I had assumed he was a Taiwanese musician and felt that he was excellent both as a composer and lyricist. His works were a breath of fresh air and the artistes he worked with, including Micheal Wong(光良), Yoga Lin(林宥嘉), Stephanie Sun(孫燕姿), Cheer Chen(陳綺貞) and Fish Leong(梁靜茹), all projected a different aura. So he was someone I’ve always wanted to meet, but the opportunity never arose. A few years after hearing about him, I learned through Chelsia Chan(陳秋霞) that Phang was in fact an overseas Chinese from Malaysia. No wonder I could not find him, I was searching in the wrong places.

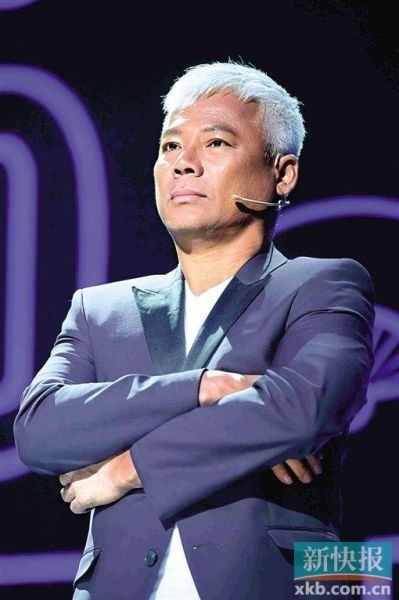

I’ve only met Phang twice and we had exchanged no more than a few sentences. Our communication happened mostly via email and Facebook. You could say we were a typical pair of online friends. The first time we met was in Taipei at a dinner event. At that time, he was Z-Chen’s manager, spoke little that night and sat quietly beside Z-Chen. We shook hands and exchanged contact numbers, and I left with the impression that he looked more like an intellectual. The second time we met was at Chelsia Chan’s home in Kuala Lumpur. While conversing with him, I found him to be a thoughtful, humble person who spoke articulately.

Recently, he has once again assumed the role of a music creator and producer with the launch of his new album “I Was Here” in Malaysia. Given that Phang rarely releases an album, and that I’ve also been wanting to write a piece on the development of Chinese music in Malaysia, speaking to him was the natural choice.

◎Where is your ancestral home? And what is your native language?

Phang: My ancestral home is in Haifeng County, Guangdong. I’m from a Hakka family, but spoke Mandarin with my parents since childhood, which meant I didn’t get to learn Hakka. I studied in Chinese schools from the elementary to high school level (Chinese high schools in Malaysia are called Chinese independent high schools), Mandarin has always been the primary language of my education. Although Malaysia’s official and national language is Malay, I still use Chinese in my daily life, switching to English or Malay only when I’m speaking to Malays, Indians or English-educated Chinese people.

◎In Malaysia, every ethnic Chinese speaks several languages, like Mandarin, Cantonese, Hokkien, Teochew, Malay and English. Did this multicultural environment influence the way you made music?

I feel that my music was influenced partly by contemporary Taiwanese songs from the 80s, and also partly by Cantonese and Western songs from the 80s. Even though I was born in a multilingual environment, I used mostly Chinese. I do often listen to Hokkien (Taiwanese), Hakka, Cantonese and even Malay songs, but I still do believe that I grew up in a monolingual environment.

◎What influenced your music? What did you grow up listening?

Mostly Taiwanese campus songs covered by Taiwanese, Singaporean and Malaysian singers. I also listened to the Carpenters, Donny and Marie[1], and Agnes Chan[2] singing western songs. In high school, I began listening to a lot of Chinese and English songs from the 80s, such as works from the Rock Records and UFO Records era, as well as Hong Kong’s Alan Tam, Danny Chan, Chelsia Chan and Anita Mui.

I also listened to plenty of charted western songs from 80s. I remember when the papers would publish the US Billboard and UK Cashbox’s Top 10 Hits every weekend. I would always collect clippings of these lists and put them in my pencil case. When I was bored in class, I would take them out to memorize. I also used cassettes to record the songs I liked when the radio stations played them, so I was pretty familiar with western pop songs then.

Note 1: Donny is a singer who went solo after leaving the Osmonds, a music group which can be considered to be the “white” version of Jackson 5. He teamed up with his younger sister Marie to form Donny and Marie, which was extremely popular in the 70s. In addition to album releases, they also had their on TV show.

Note 2: A Hong Kong singer who left for Japan in the 70s to build her career. She now lives in Japan and has been releasing albums and giving performances in recent years.

Note 3: The UK had the Gallup and Cashbox charts in the 80s. Both were sales-based, but their placings were sometimes different. These charts have since been replaced by Music Week’s chart.

◎How did you join this industry? Who helped you in your career?

During my fourth year of studies at the National Chengchi University’s Department of Journalism, I took part in the school’s Golden Melody competition and was spotted by the producer Preston Lee(李安修), who was then serving as a judge for the competition. With his referral and right after graduation, I became a production assistant at Music Impact Entertainment, where he was the planning manager. Many people helped me in my career, other than Preston Lee who got me into the industry, there was also Yiu-Chuen Chan(陳耀川) (composer and producer of songs like “Forget Love Potion”, “An Old Love Song”, “Flower of the Woman”), my boss in the production department, who took great care of me.

◎To my knowledge, Eric Moo was the first Chinese Malaysian singer to move to Taiwan for his music career. How do you view his influence on the Chinese Malaysian singers who came later? Did anyone came before him?

Eric Moo(巫啟賢) can be considered a success, but there were Malaysian singers who released albums in Taiwan before him or around the time he was active, such as Paul Wah Chew(周博華) and Wang Weisheng(王威勝). Perhaps the lack of publicity or management limited their potential.

I feel that Moo’s impact on later generations comes mostly from the confidence and motivation he has given to Malaysian musicians or singers who wished to venture overseas. But credit must also be given to another Malaysian, Liu Mingrui (“A Wordless Ending”, “Love Too Late in Coming”), for his works also enjoyed a high level of circulation in Taiwan.

◎Why did you return to Malaysia at the peak of your career?

I returned to Malaysia in 1998. I was merely involved in production work in Taiwan and I wasn’t actually peaking (haha). After spending eight years studying and working in Taiwan, I was kind of homesick, and I didn’t adapt too well to Taiwan’s weather, as well as the culture and politics of the industry. There were also some potential personnel issues (Music Impact had sold its record business to BMG), so I decided to return to Malaysia.

◎In the last decade or so, many Chinese Malaysians have left for Taiwan, China or Hong Kong. Do you see this as a natural trend, or perhaps because Malaysia itself doesn’t offer the opportunities they want?

For Malaysian singers and musicians, this is a matter of one’s developmental phase. It’s like going to college after high school, things will be different. Moreover, a stint overseas can raise your value and worth when you return to Malaysia.

About the differences between Malaysia’s local music industry compared to elsewhere, you can still find the space and opportunities to live on if you position yourself properly, but it really is a question of value.

◎What are your thoughts on digital music? Did the emergence of digital music help Chinese Malaysian singers and musicians?

I don’t have enough information on this, but I’ve indeed noticed the rapid changes affecting how an entire generation watches and listens to music. Take myself for instance, although I still do listen to CDs and vinyl records often, it’s more like a form of “appreciation”. I now usually rely on my Spotify playlist to listen to songs, or I would look for singles to listen to, instead of entire albums like I used to.

Young people are way different, they tend to prefer stronger visual elements. Artistes who worked in the industry when the internet emerged found it impossible to control their exposure, and this is true no matter if they are veterans or newcomers. You could be acting, singing or doing quirky stuff, and many things would be out of your control (examples of successfully engineered campaigns also exist). An awkward situation we have now is that internet celebrities are often more popular than artistes on social media, yet businesses judge the popularity of artistes based on popularity rankings on the social media. This makes it tougher for us to manage and plan a Malaysian singer or musician’s career. Maybe we will need to rethink our approach to the new media? The old established theories on managing the record business are now being challenged.

◎Why did you found Pocket Music?

◎Why did you found Pocket Music?

I released my solo album “Finding Percy Phang” not too long after returning to Malaysia. While doing promotion work for the album, I discovered that my philosophy to doing music was similar to my colleague Lin Lifen’s. She worked on publicity in the distribution company for my album. When she left her record company, she and I founded Pocket Music, which releases non-pop music works in addition to other music-related ones. For example, we helped the Dandelion Choir, a music group comprising teachers and students, to release their performance albums, which included children’s songs, covers of old songs, soul music and original songs. We also worked with some student-run magazines to create campus music.

◎It’s already difficult to manage a music production company in Malaysia, and even more so if you’re doing Chinese music. Could you share with us the company’s growth journey and some memorable experiences?

Right now, our primary business is music coordination and we serve mostly TV station clients. We are also involved in adverts, TV program music, as well as various forms of music production and music copyright. We did encounter some cash flow issues when we accepted major deals while we were still small, but we were fortunate enough to have an excellent manager as a colleague. The company had a simple structure, personnel costs were very low, and we were also not huge spenders, so the company tided over even though we did not see huge profits.

◎You’re the boss, producer and also the manager. Can it get confusing with so many roles?

It’s tiring to hold so many positions. But in this current climate, not doing a bit of everything would lead to problems with budget control and results. If I’m too selective about my job scope, such as concentrating on only one job like production or songwriting, I will not survive. I’ve lightened my management workload in the past few years though. Sometimes, I naively imagine myself writing songs for a living just like Chen Xiao-xia or Daryl Yao.

◎Ever thought about what you would do if you were not doing music?

I’ve thought about it. But all these years, I’ve been so focused on music that I haven’t learned enough of anything else, so I’m no longer interested.