Existential crises seem to make for the vast bulk of human existence as the year approaches 2020. A casual scroll through the various social media platforms at our disposal will tell you as much.

What is our purpose?

Why are we here?

What's the point?

Though humanity has asked these questions since our minds had the capacity to formulate them, life, now more than ever before it seems, is and endless cycle of trying to figure these out, thinking we've got it, and then realizing that we really don't know anything at all.

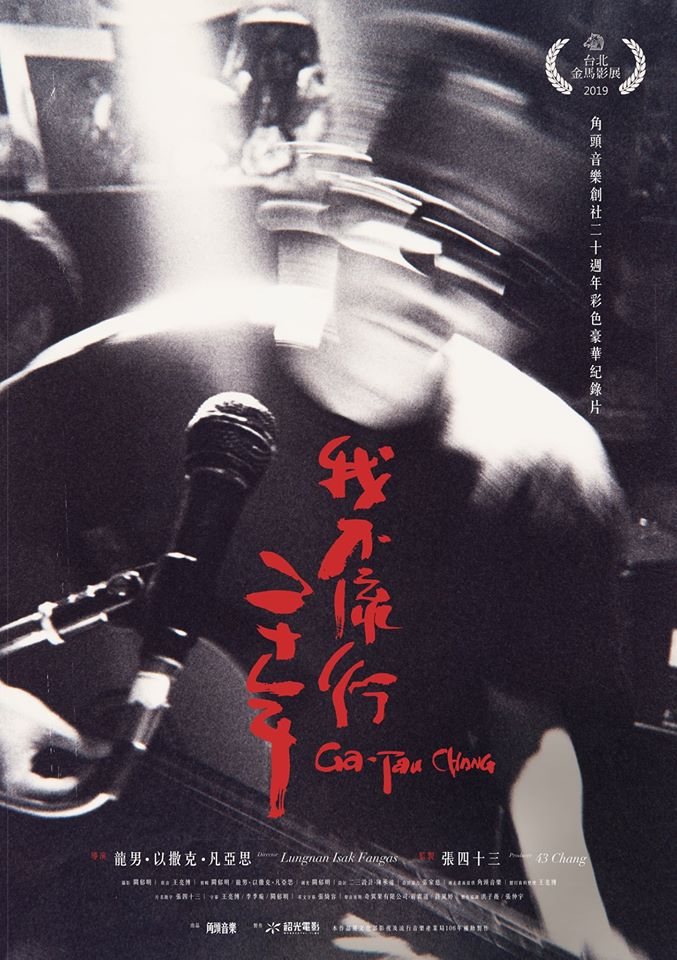

What happens when this terrible moment of realization hits is the central pillar of Gatau Chang, a documentary that follows the lifespan of Taiwan Colors Music (TCM) and its founder, Chang 43.

For the past two decades, Chang, now somewhere around 50 years of age, has made an institution of TCM. He broke the likes of Mayday, The Chairman, Quarterback. He introduced Taiwan to a multitude of previously undiscovered aboriginal recording artists such as Panai and Paudull, who brought TCM its first win at the Golden Melody Awards, taking many from village obscurity to their first big city stages.

Over the course of 20 years, Chang has helped bring Taiwanese music—true, original, local Taiwan born-and-bred indie rock and aboriginal folk music—from infancy to adulthood. He by no means did it alone. But now, after amassing a catalog of about 60 albums and putting on countless festivals and events, such as the yearly Ho Hai Yan Festival at Fulong Beach, a gargantuan undertaking that draws revelers in their tens of thousands, Chang is tired. As B.B. King sings, "The thrill is gone." He wants something else, something new. But what?

Well, what Chang wants, as the opening scene makes clear, is to sell the label, preferably for as much as he can get. And if that means selling out to a foreign concern, and thereby potentially alienating the label's homegrown fan base in the process, so be it. He just wants out; to move on to the next thing, with enough cash lining his pockets to be comfortable, secure.

Whoever the buyer might be and where they come from—those things aren't important. Chang is a man who has given everything he has to his dream, and the dream has in turn taken everything he has to give without thought for replenishing his reserves of energy, passion, or compassion. After 20 years, as Chang says, "I've given enough," a statement echoed by many of his closest friends, coworkers, and collaborators.

The story weaves from past to present. There is Chang, the young upstart, putting together his first compilation album, poring over recording details in a dimly-lit, poorly-furnished Taipei recording studio. Here he stands at 50, speaking of how in his youth he admired the local gangsters and their culture, how they did anything they wanted whenever they felt like it, and how he dreamed of running a music label in exactly the same way.

Chang calls up old friends and collaborators, seeking advice, words of wisdom, direction. He and Qing-Yang Xiao, the graphic designer who brought TCM its first Grammy nomination in the packaging category, meet up for beers, speaking for the first time in more than half a decade. They laugh, reminisce. Xiao uses Motown Records as an example for Chang to follow, a label that thrived in the music industry's heyday, only to fall hard and fast by the nineties, staying alive by the grace of being sold to Universal.

"You can sell and have more in your life than just the label," says Xiao. Chang nods. For the first time on camera, he uses the words "mid-life crisis" to describe what he's going through.

Chang then takes a trip to Taitung, reuniting with old friend and collaborator Paudull, as well as Jye Renn, TCM's early musical director, the man who brought many aboriginal artists such as Paudull, Samingad, Hao-en, Jia Jia, Long-Ge, and the Nan Wang Sisters to Chang's attention. They cast their lines near the Southern Dulan Cape, Chang struggling with his form on the rocky beach. As the sun beats down they remember the good old days, putting out six albums a year though they struggled to shift even a thousand units of a single recording. Chang laments that he doesn't want to end up like Crystal Records, a forerunner that inspired him to start his own label, now largely forgotten even among Taiwan's hardcore heads.

Chang has trouble letting go, that much is clear, but if he doesn't, by his own admission the business could tank within another ten years. Album sales, once fifty percent of his profits, have shrunk year on year. Now, he says bitterly, TCM is more an event company than a record label. Festivals and concerts are their bread and butter.

Later, around the dinner table in Taitung's Nan Wang Village, the place many of Chang's aboriginal singing stars came from, Renn tells Chang he can see that his passion is still there. TCM still has relevance, he says. It provides a space for truly local expression. Forward Music sold for a hefty sum. Chang wants that too. Or does he? Will he later regret selling out, once it's too late? The question remains up in the air, looming, lingering like a black cloud.

There are so many conflicting needs in the man, expertly explored as the camera captures his every anguished musing, the pursed lips, the tsking sound he makes when vexed, the crook of his head to the side as he ponders yet another query that lacks the straightforward yes-or-no reply he so desperately desires; an answer that can only come from somewhere inside himself, a place he has yet to find. There is no point, he decides, of moving on unless he knows what he'll move on to will exceed in terms of success that which he has already done.

The last time Chang quit something, after all, was in 1996, when he signed off his radio show, "Rock and Roll At Night," for the last time before leaving to start TCM. To close out the program, Chang picked up an acoustic guitar and sang "Proverbs of Love" by Lo TaYou. "I gave you my life," he crooned softly, "no one can understand what love truly is, love used to be you and me, yet I gave myself to you."

It is a song at once about the love between two people and the devotion Chang feels for the thing that has been the only constant love in his life, ever the lone wolf, sure that if he were to share his time, his space, his mind with another person, he would only annoy them. You can have the perfection of the life, or the perfection of the work, not both. Chang made his choice long ago, for better or for worse.

Over the years there has been chaos and there has been controversy. Chang himself says he wasn't a good manager, never skilled at the everyday ins and outs of telling people what to do and when and how. He was the man with the dream—the type of person as flawed as he is driven to succeed. The question arises of whether he underpaid the aboriginal singers he brought to stardom. All he can say is that he kept his promises, every one of them.

No matter what happened, he and they seem to be on good terms. In Taipei, Chang sees Panai at the scene of her long protest in front of the capital's Presidential Hall, calling for indigenous rights and land reform. At that point, she had been staging the sit-in for 812 days. "How can I give up?" she says to Chang when he questions why she goes on. "What would I tell my kids to do when times get tough?"

And therein Chang has his answer. What comes next is not about exceeding what he has done before. It's about exceeding the way he has thought about his life—his philosophical and existential bedrock is in need of a seismic shift. Where that shift will take him remains to be seen.

At a concert in Kaohsiung, celebrating TCM's 20th anniversary, Paudull reminds Chang of this, lauding him from the stage, talking of how all those years ago he told Chang his music wasn't commercial. Chang would never get rich putting it on the market. Chang's response? He didn't care. He wanted to run his label like a gang boss, after all, a "gatau," doing what he wanted, when he wanted.

A lot has changed since then, but Chang 43 is still the same man. Still searching. Still seeking the answers to those same old questions. One of those questions looms larger than others, even as the screen fades to black: What now?